"Give Me Your Poems"

Three days ago, Lyubomir Levchev came to read on campus, in celebration of National Poetry Month here in yankville. Lyubomir is a Bulgarian poet, and this was his self introduction:

hello my friends, of famous rogers williams college.

I am lyubomir.

I dont speak english.

But after 2nd bottle, I speak english.

Sitting there with notepad and cranberry juice, I couldn't take my eyes off the old man: he has one of those faces that time's used like it would an old tree trunk-- wrinkles, warts and mottled skin like lichen and moss and owls nest in the top branches. He has the most beautiful smile, and carries his cane instead of leaning on it. He came with his lovely wife, his translator, and his publisher and friend, Alexander Taylor, one of the directors of Curbstone Press, and a poet in his own right.

Something about Lyubomir caught my imagination: I have never scribbled down so much verse thanks to the presence of one old man, ever before. His publisher read Levchev's work in english, and then the poet would read the same in Bulgarian:

He tells his translator,

no stopping.

Refuses to read, like a 5 year old

at his eye doctor's clinic,

and holds his cane

while listening,

like a flower.

Levchev wanted Taylor to keep reading, while he sat there and listened, intently.

What a face!

If only this pen was a brush,

and I, Rembrandt.

He could've sat in a boat

on a wharf

in a ditch,

reading poetry with a pipe.

He smiles.

What a face!

I mourn my lack.

Lyubomir only picks up his cane

and points to the poetry growing

outside the window.

I kept scribbling things like this throughtout the two-hour reading. Levchev has written some fine poetry. The official blurb on him, according to the PEN American Centre is as follows:

Lyubomir Levchev was born on April 27, 1935, in Troyan, Bulgaria. He has published over 20 volumes of poetry and two novels. Over 60 of his books have been published in 33 countries. He has been awarded the Gold Medal for Poetry of the French Academy and the title Knight of Poetry, the Grand Prize of the Alexander Pushkin Institute and the Sorbonne, and the World Award of Mystic Poetry Fernando Rielo. Levchev is the founder and editor of the international literary magazine Orpheus.

Taylor, while introducing Levchev, said that the President of Bulgaria visited him, and that he was the lion of Bulgarian poetry. Hearing this-- albeit translated-- Levchev let loose a loud belly laugh, rocking back and forth in his chair in his merriment. His translator then said to us, "he says, 'very well if you say so'". Little things like this kept the audience charmed throughout the reading.

The first poem that Taylor read, was called 'Lullaby', and is translated from the Bulgarian by Valentin Krustev:

Lullaby

by Lyubomir Levchev

The boy was standing at the exit

of the new gas-station

like a deadlock,

like a gas pump,

like an air hose.

I braked suddenly to pick him up.

And only then did I notice

what an evil appearance he had.

I asked him:

“Which way?”

“To Plovdiv,” the hitch-hiker grumbled.

“Eh!” I joked bluntly like an intellectual.

“Such a young boy

to such an old city!”

“Oh, fuck this face of mine!

Could you, too, guess

that I still have no ID card?”

“But why are you cursing?”

“Because they won’t give me a job.

I can’t get started.

Do you know what it’s like

to be

and yet be unable to make a start?…”

I gave him a piece of chocolate.

He ate it up at once

and fell asleep.

I watched him, just in case,

in the rearview mirror,

rocking

in the loop of sleep.

His hair, long as a wig,

made him look like

a premature Robespierre.

And so we flew across eternity

like two centuries,

like two tenses:

past continuous

and a future that cannot begin.

Meanwhile the whirling wind hummed a lullaby:

Sleep, sleep, my boy.

It’s not your fault,

But our shameless falseness.

Sleep, but don’t trust Fukuyama.

History exists.

History is searching.

And soon

it will find you a job.

Oh, what a job!

They will remember you!

Levchev is part of the 'PEN World Voices: The New York festival of International Literature' which will be on from April 25-30. He will be there along with Chinua Achebe, Martin Amis, Upamanyu Chatterjee, Russel Banks, Margaret Atwood, Salman Rushdie and others.

I bought his latest book, "Ashes of Light", and went up to say hello to him. He looks at me, takes my wrist in his hand and greets me in the old-fashioned way:

To say hello,

he lifted the back of my hand

to his nose and moustache.

Reverent aged touch.

Automatic, I would've done

the deep namaskaram,

shishya arriving after a long journey.

He prevents action by

gripping my hand and growling

"give me your poems"

Breathless, I read him my scribblage.

I gasp out, "this has not happened before"

Yes, he smiles. This is how it starts.

That's exactly what he said: "Give me your poems". After reading a little of what I had written for him, he kissed my cheek and said, "thankyou". I cannot describe that moment well enough: everything came together, Levchev was an angel, the afternoon sun blazed in from the windows and my pen would not stop moving.

There was a conversation on poetics, as can be expected. Levchev spoke on translation, how he felt translation was a separate art by itself. He also said that if the translation sounds better than the original, then the translator has failed. Both Taylor and Levchev agreed that the literal meaning was not as important as the true sense and feeling of what the poet is trying to convey. Taylor quoted an anecdote that's attributed to some hispanic author whose name eludes me: a student once ran up to this great author with a translation and asked eagerly if it was right. The author in turn said yes, it is right, but the aroma has gone.

Levchev drew a self portrait in my copy of his book for me. He told me he has visited India twice, and loved the ashram at Pondicherry. I told him I had a Bulgarian friend I had met down in New Orleans. He clapped me on the shoulder, and smiling, rumbled in Bulgarian to his translator, who turned to me and said, "ah, now he says you are family".

Out of all the poems Taylor read, two poems by Levchev made a lasting impression. One was, called Tomorrow's Bread.

Tomorrow's Bread

Once I reproached my son

because he did not know

where to buy bread.

And now...

he is selling bread

in America.

in Washington.

In his daytime routine

he teaches at the university.

At night he writes poetry.

But on Saturdays and Sundays

he sells bread

on the corner of Nebraska and Connecticut.

...

In Sofia

the shades of old women

scour the dark.

Ransacking the rubbish bin they collect bread.

Pointing at one of them, a teacher

of history and Bulgarian language, they say:

"Don't jump to conclusions, take it easy!

She's not taking the bread for herself. She feeds

stray dogs

and birds."

And my words too are food for dogs

and birds.

Oh God!

Why am I alive?

Why do I wander alone in the Rhodopes?

Why do I gaze down abandoned wells?

Why do I dig into caves where people lie?

And pass the night in sacred places, renounced by you?

I am seeking the way

to the last magician's hideout,

he who forgot to die

but has not forgotten the secret of bread.

Not today's bread, which is for sale,

not yesterdays bread which has been dumped...

I must know the secret of tomorrow's bread.

The bread we kiss in awe.

The bread that takes our children by the hand

and leads them all back home.

You wrote of bread,

and your son who sells it

at the corner of Nebraska and Connecticut.

You wrote of Sofia,

old women finding bread in dust-bins,

and your son, and no bulgarian bread in sight.

I wept silently,

thinking of my professor, Cyrus Partovi,

who will not return to Iran

but misses his mother's

bread.

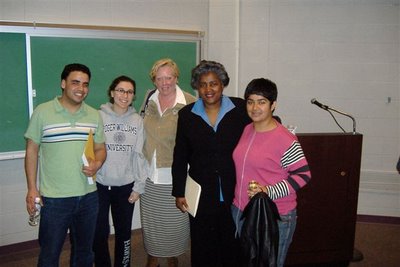

We took plenty of pictures, which the media person said she'd send over in a few days time. He stopped smoking two years ago, for health reasons. But he stole a smoke from his wife, as she, the translator, the publisher and I stood outside the library, waiting for their ride to come up. For Priyanka, he said. Mike and Alex and some of the others came out then, and we exchanged hugs, and cards, and email addresses.

"To PriYanka- poet

From LYubo

20.04.06"

He wrote it like that, Y's overlong. I asked him to come to India again. He crossed himself, with a little half-smile, half-nod.

I hope he makes it.